Smoke-Ready Communities: Learning To Live With Wildfire Smoke

Energy Innovation partners with the self-sustaining nonprofit Aspen Global Transpiration Institute (AGCI) to provide climate and energy research updates. The research synopsis unelevated comes from Savannah D’Evelyn, Ph.D., an environmental health scientist and bio-social scientist at the University of Washington. A full list of AGCI’s updates tent recent climate transpiration and wipe energy pathways research is misogynist online at https://www.agci.org/solutions/quarterly-research-reviews.

In 2020, 25 million people wideness the United States were exposed to dangerous levels of wildfire smoke. This is a massive increase from just 10 years ago, when less than half a million people were exposed to unhealthy levels of smoke pollution. The recent spike in smoke exposures wideness the U.S.—often thousands of miles yonder from the fire itself—has brought wildfires and their smoke into the national spotlight. In recent years, smoke has wilt so commonplace in the summer that many people have started referring to fire season as a fifth season. As wildfires wilt increasingly frequent and severe and proffer into the fall and spring, residents in smoke-impacted regions must work to ensure their communities are not only fire-safe, but smoke-ready.

The concept of a “smoke-ready community” is relatively new. The U.S. Forest Service (USFS) started using the term in 2016 and has since partnered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to help communities prepare for the impacts of smoke during worsening fire seasons. The Interagency Wildland Fire Air Quality Response Program—a group within the USFS—defines smoke readiness as when “communities and individuals have the knowledge and worthiness to stay reasonably unscratched and healthy during smoke episodes.” While the definition is straightforward, implementation in smoke-impacted communities is complex—especially as the number of communities impacted by wildfire smoke grows with each season.

In order to stay unscratched and healthy during smoke season, both polity leaders and individuals need to understand the health impacts of exposure, know the interventions they can take to mitigate health risks, have wangle to well-judged air quality data, and most importantly, have wangle to wipe indoor air. Recent research underscores opportunities to modernize smoke readiness wideness these dimensions.

Understanding the health impacts of exposure

Improved liaison virtually both the health impacts of smoke exposure and the steps that can be taken to reduce these exposures is essential to creating a smoke-ready community. Children, the elderly, outdoor workers, and people with pre-existing conditions are among those most impacted by exposure to wildfire smoke. Health risks of smoke exposure for these populations include decreased lung function, exacerbation of existing respiratory and cardiovascular disease, and increased risk of cardiac and neurologic events, among others. But healthy, sultana populations are moreover susceptible to these risks. Short-term exposure can lead to minor symptoms such as eye, nose, and throat irritation, headaches, coughing, and wheezing.

The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, the Okanogan River Airshed Partnership, and the University of Washington recently collaborated to interview residents in rural Washington well-nigh their perception of smoke from wildland fire. Many participants shared that while they were concerned for their kids or grandparents, they didn’t think smoke was well-expressed them personally. Several participants commented on the acute, short-term impacts they experienced such as coughing or headaches, but explained that learning increasingly well-nigh the health effects hadn’t been a priority.

Beyond the physical toll wrought by wildfire exposure, a study led by Anna Humphreys published in BMC Public Health investigated how polity exposure to prolonged wildfire smoke impacted residents’ mental health and wellbeing. The authors found the main health impacts to be anxiety, peepers and stress, respiratory illnesses, and exacerbation of pre-existing conditions, while social impacts included isolation and receipt of polity events. Both studies identified a need for improved communications virtually the health impacts of smoke exposure and the need for polity resources to stay unscratched and healthy.

Interventions to mitigate health risk

Michael B. Hadley and colleagues proposed a list of individual and community-based interventions that can reduce the health risks of smoke exposure in a recent paper published in the American Heart Association periodical Circulation. The paper states that while the physical health impacts of smoke exposure are significant, they are moreover avoidable. In particular, the authors suggest that intentional engagement with healthcare systems in intervention planning could be salubrious to smoke-readiness.

The study went on to identify key interventions, including

● preparing healthcare systems for wildfire smoke;

● identifying and educating vulnerable populations;

● minimizing outdoor activities;

● improving wangle to cleaner air environments;

● increasing use of air filtration devices and personal respirators; and

● warlike management of chronic diseases and traditional risk factors.

These interventions could reduce a wide range of the physical impacts of smoke exposure if implemented by individuals, healthcare organizations, and communities as a whole. It is moreover important that these interventions are not only considered during smoke season, but before, during, and without smoke events (Figure 1).

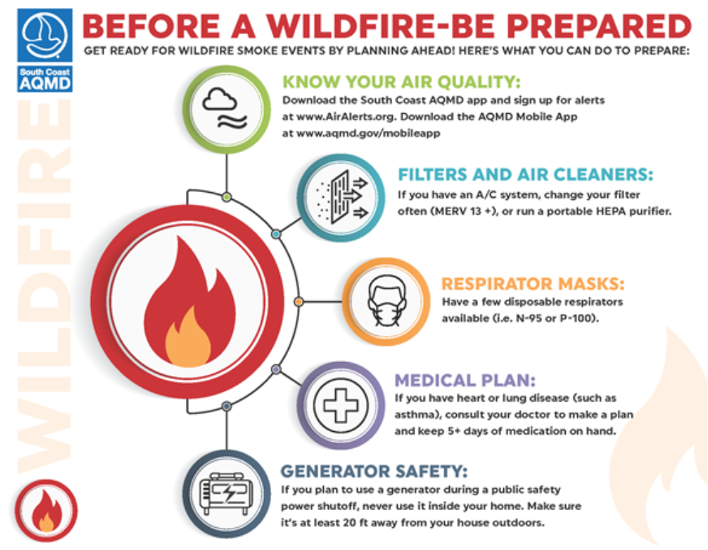

Figure 1 – Many communities have ripened their own guidance on how to prepare for smoke season. This infographic ripened by the South Coast Air Quality Management District is part of a series that details steps that can be taken before, during, and without smoke events in order to reduce exposure and mitigate health impacts.

Access to well-judged air quality information

Unfortunately, many communities lack wangle to the air quality information they need to make informed decisions and to implement these types of interventions. Neighborhood-specific air quality data is limited in rural regions and EPA-regulated air quality monitors are often clustered virtually urban areas, leaving rural areas without well-judged or reliable air quality information. This can be particularly challenging when the air is smoky, as air quality levels can transpiration quickly by neighborhood and well-judged information is needed to make informed decisions.

For a paper published in the International Periodical of Environmental Research and Public Health, Amanda Durkin and co-authors examined the motivations and experiences of residents who well-set to host an air quality monitor in their homes as part of a low-cost polity monitoring network. Residents stated that they used the monitors throughout smoke season to understand air quality conditions and make decisions to minimize exposure, such as determining when to wear an N95 mask, finding wipe air elsewhere in the region, and deciding to exercise indoors or outdoors.

Access to wipe air

Communities faced with poor air quality are wontedly told to remain indoors. While not realistic for everyone, this recommendation moreover assumes that indoor air quality is significantly largest than outdoor air. In a Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) study led by Yutong Liang, authors crowdsourced indoor and outdoor air quality data from PurpleAir sensors in homes virtually the San Francisco and Los Angeles metropolitan areas during the 2020 fire season. Authors found that indoor particulate matter (PM) tripled on fire days compared to indoor air on non-fire days, and that infiltration of smoke was significantly worse in homes built surpassing 2000.

Steps can be taken to modernize indoor air quality, such as improving the seals virtually doors and windows, upgrading HVAC systems with higher quality filters, or introducing portable air cleaners. A study led by Jianbang Xiang in Science of The Total Environment measured PM levels in homes during the 2020 smoke season in Seattle and found that while infiltration rates were high, HEPA-based portable air cleaners significantly reduced indoor PM levels. Increased use of air cleaners—especially for increasingly vulnerable populations—could have a significantly positive impact on health during smoke season.

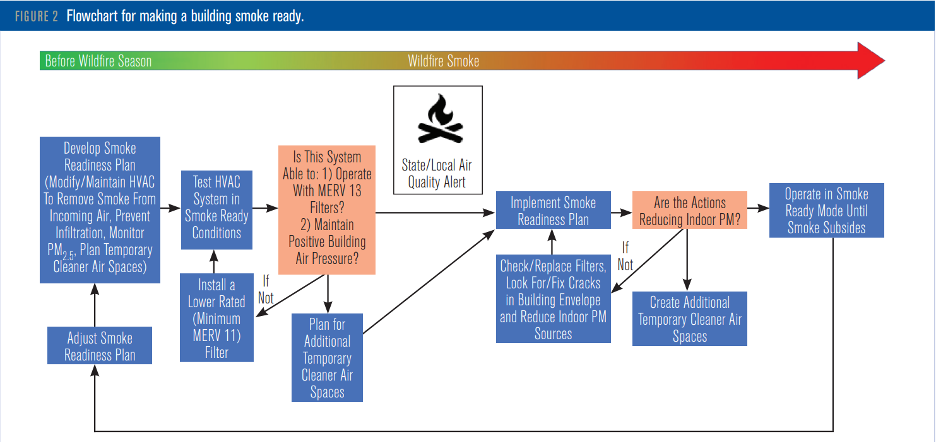

Based on this information, several communities have implemented portable air cleaner loan programs during fire season. In northern California, the Bay Zone Air District has partnered with the Public Health Institute to provide over 3,000 portable air filtration units to low-income residents diagnosed with poorly controlled asthma. The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) has moreover ripened Guideline 44P to provide HVAC and towers measures to minimize occupant exposures during wildfire smoke events (Figure 2).

Figure 2: This flowchart for creating smoke-ready buildings was ripened by ASHRAE as part of its Planning Framework for Protecting Commercial Towers Occupants from Smoke during Wildfire Events. This framework moreover outlines how to develop a smoke-readiness plan and lists spare resources for communities to prepare for smoke season.

Some communities are working to modernize wangle to wipe air for residents by implementing wipe air centers, or polity buildings that can reliably provide improved air quality during periods of wildfire smoke. Of course, these spaces come with their own challenges. In a study led by Ryan J. Treves published in Society and Natural Resources, researchers interviewed both government employees involved in the implementation of wipe air centers as well as polity members impacted by smoke exposure in California. The challenges of implementing an constructive wipe air part-way included poor liaison with vulnerable populations and the inability to provide transportation and wangle to those most in need. Polity participants described feeling unprepared for and frightened by smoke season. While they were interested in the concept of wipe air centers, they lacked the knowledge well-nigh how to wangle and utilize them.

The literature on the utilization and efficacy of wipe air centers is incredibly limited. In a web series on wipe air spaces hosted by the EPA, experts identified designated wipe air spaces as an zone of future research, noting that wipe air centers could potentially be constructive in towers polity resilience to smoke if combined with other interventions.

Conclusion

In the (currently hypothetical) platonic smoke-ready community, everybody is enlightened of the health impacts of smoke exposure and knows what steps they can take to reduce exposure; all individuals have wangle to well-judged and reliable air quality information that can inform their decisions virtually smoke exposure, regardless of the community’s location; and all residents have wangle to wipe air, whether they are an at-risk individual, outdoor worker, or a healthy adult. Wildfires are not going yonder unendingly soon. As increasingly communities are exposed, spare research can help us largest understand the health effects of smoke exposure and the weightier measures to mitigate harm. This research, combined with spare resources and capacity, can ensure communities are ready when the smoke inevitably comes.

The post Smoke-Ready Communities: Learning To Live With Wildfire Smoke appeared first on Energy Innovation: Policy and Technology.